PMS in Perimenopause – Why It Can Feel So Much Worse (and Why You’re Not Imagining It) (part 1)

If you’ve reached your 40s (or even late 30's) and noticed your PMS feels more intense, more emotional, or more unpredictable than ever before, you’re not imagining it. Many women describe feeling unlike themselves for days or even weeks at a time, then spending the rest of the month trying to recover or make sense of it.

The reassuring truth is: there is nothing wrong with you. Your brain, hormones, stress system, and immune system are simply navigating a very turbulent phase of life — perimenopause.

Here’s what’s really happening.

1. What PMS Actually Is — and How PMDD Fits In

PMS

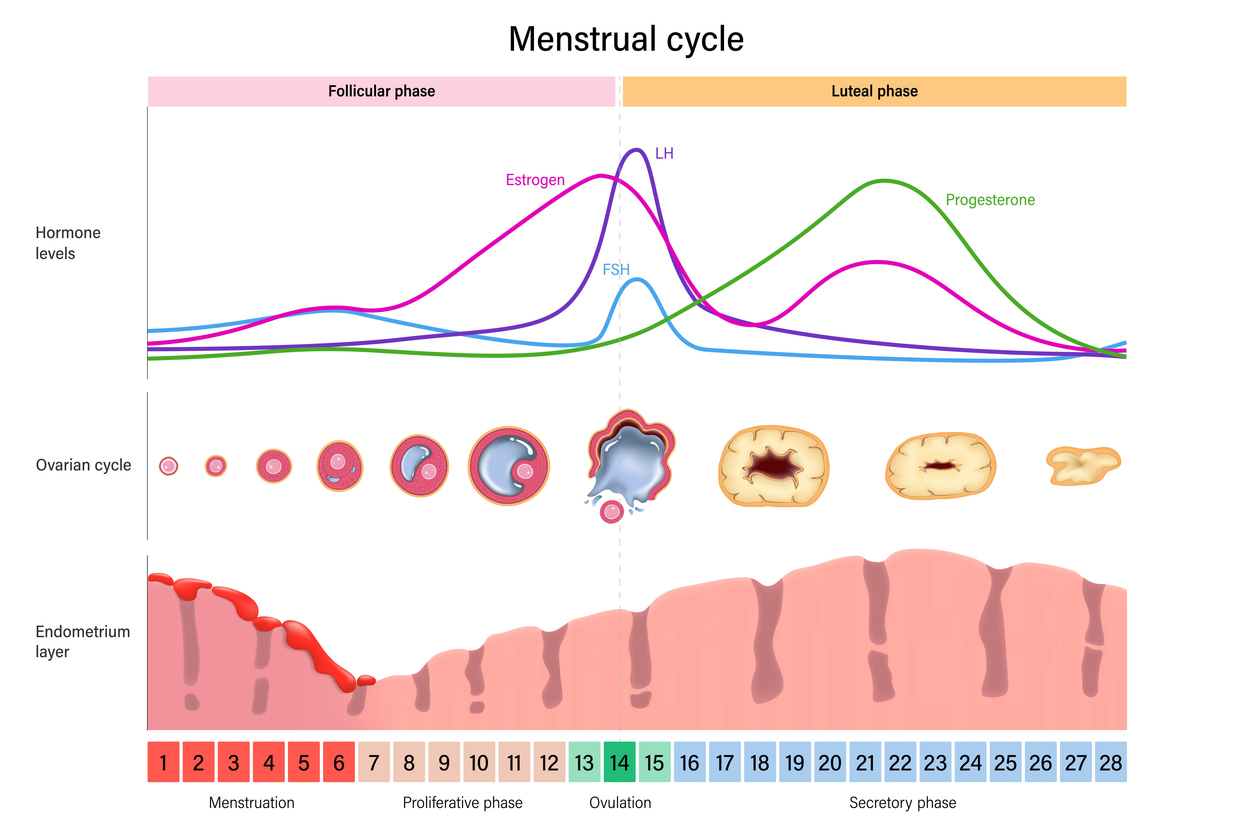

Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) is a cyclical pattern of emotional, physical, and mental symptoms that show up in the luteal phase (on average, the 2 weeks before your period) and improve once bleeding begins [1].

Common symptoms include:

-

Mood swings, irritability, tearfulness

-

Anxiety or inner tension

-

Brain fog, difficulty concentrating

-

Bloating and breast tenderness

-

Headaches, cravings and fatigue

PMS varies in severity from woman to woman, but it is very common.

PMDD

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) is the much more severe end of the spectrum. It involves:

-

Intense mood symptoms (severe depression, anxiety, rage, or hopelessness)

-

At least five symptoms, including one mood symptom

-

Significant disruption to daily life, work, or relationships

PMDD is officially recognised in the DSM-5 as a mood disorder [2,3].

Both PMS and PMDD are rooted in the brain's sensitivity to normal hormonal changes, not “bad hormones” or imbalance [1,4].

2. Why PMS Happens in the First Place

Contrary to what many women are told, PMS is not usually caused by abnormal hormone levels.

Instead, it’s caused by how your brain reacts to the monthly rise and fall of oestrogen and progesterone.

Let’s break down the biology in a simple, empowering way.

a) Hormonal changes + a sensitive brain

During a normal monthly cycle:

-

Oestrogen rises before ovulation, dips, rises a bit again, then falls

-

Progesterone rises after ovulation, then drops sharply before your period

Most women’s brains handle these changes smoothly.

But in PMS/PMDD, the brain is much more sensitive to these hormonal shifts [1,4,5].

One key player here is allopregnanolone (ALLO) — a brain chemical made from progesterone.

What is ALLO?

ALLO is a calming neurosteroid — a substance your brain makes that helps regulate mood, stress, and relaxation. It acts a bit like a natural anti-anxiety signal.

How ALLO affects mood

ALLO works by stimulating GABA-A receptors, which are part of your brain’s main calming system.

What is GABA?

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is the brain’s primary “slow down and settle” chemical.

You need GABA to:

-

Relax

-

Manage stress

-

Sleep

-

Feel grounded rather than wired or overwhelmed

In PMS/PMDD, the brain becomes less responsive to ALLO as it rises and falls [4,6].

So instead of feeling calm, you may feel:

-

Agitated

-

Anxious

-

Irritable

-

“On edge”

This is a biological sensitivity — not a personality flaw.

b) Neurotransmitters: serotonin, GABA, and more

Hormones constantly interact with your neurotransmitters, which are the chemicals your brain uses to communicate.

What is serotonin?

Serotonin is the neurotransmitter that helps regulate:

-

Mood and emotional well-being

-

Appetite and cravings

-

Sleep

-

Motivation and resilience

In PMS, serotonin activity drops or becomes less stable [1,4,7].

This is why many women:

-

Cry more easily

-

Feel low or irritable

-

Experience cravings or emotional eating

-

Have trouble sleeping

SSRIs (antidepressants) help some women with PMS/PMDD because they increase serotonin and appear to improve ALLO’s calming effect on the brain [4,7].

c) Changes in brain circuits (amygdala + prefrontal cortex)

Modern imaging studies show that women with PMS/PMDD have differences in key emotion-regulating regions:

What is the amygdala?

The amygdala is the brain’s emotion-detector. It helps identify threats and triggers fear, anger, or anxiety responses.

What is the prefrontal cortex?

The prefrontal cortex is your rational, planning, problem-solving “CEO brain”. It regulates emotions and helps you put things in perspective.

In PMS/PMDD, hormone shifts can make:

-

The amygdala more reactive

-

The prefrontal cortex less effective at calming stress

This is why tiny frustrations feel huge just before a period — your brain’s emotional alarm system is more sensitive [5,8].

d) A stress system that’s easier to overwhelm

Your HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis) controls stress hormones like cortisol.

In PMS/PMDD, the HPA axis is more reactive and slower to settle down [5,9].

This means stress hits harder, lasts longer, and is more likely to spill over into mood symptoms.

Trauma history, burnout, and chronic stress make this system even more sensitive.

e) Inflammation and gut–brain changes

Studies show PMS is associated with:

-

Increased inflammation

-

Increased oxidative stress

-

Changes in gut permeability (sometimes called “leaky gut”)

-

More immune activation in the luteal phase [10,11]

These changes are linked with:

-

Fatigue

-

Physio-somatic symptoms

-

Anxiety and restlessness

-

Breast tenderness

-

Cravings

It’s a whole-body condition — not “all in your head”.

f) Genetics

PMS and PMDD run strongly in families.

Genes affecting:

-

Oestrogen receptors

-

Serotonin signalling

-

Calcium channels

-

Stress responses

all influence how sensitive your brain is to hormone change [12].

This is why one woman breezes through her cycle while another struggles — it’s wired at a biological level.

3. What Happens in Perimenopause?

Perimenopause is a hormonally chaotic transition, usually starting in your 40s, where initially cycles may look “normal” but are biologically very different.

Key changes include:

-

Large, erratic swings in oestrogen (much bigger than in your 20s or 30s)

-

Inconsistent progesterone due to weaker ovulation

-

Cycles that become shorter, longer, or unpredictable

These shifts can worsen PMS even when periods still seem regular on the calendar [13–15].

Research also shows PMS is about twice as common in women with irregular cycles compared with regular cycles [16].

4. Does PMS Always Get Worse in Perimenopause?

No.

Here’s what the research shows:

-

A large population study found PMS actually decreases for many women with age [17].

-

Women with a history of depression or trauma often experience worsening symptoms [18,19].

-

Some studies show no major change, just different patterns [20].

In short:

PMS worsens for a subset of women with certain vulnerabilities.

Others stay stable or even improve.

5. Why PMS Worsens in Perimenopause (for Some Women)

a) Bigger, faster oestrogen swings

Oestrogen becomes far more unstable in perimenopause.

Some women are sensitive to:

-

Oestrogen rises

-

Oestrogen drops

-

Any rapid change at all [18,19]

For these women, the hormonal “rollercoaster” of perimenopause is especially challenging and triggers stronger premenstrual symptoms.

b) Less predictable progesterone and ALLO patterns

More anovulatory cycles = more inconsistency in:

-

Progesterone levels

-

ALLO levels

-

GABA-A receptor responsiveness

This means emotional symptoms can be:

-

Strong one cycle

-

Mild the next

-

Back with a vengeance the following month

If you’re sensitive to progesterone or ALLO, you’ll feel this instability more intensely [4,6].

Some women also react strongly to synthetic progestogens used in menopausal hormone therapy [21].

c) Stress becomes harder to regulate

Hormone fluctuations make the stress system (HPA axis) less stable.

This can show up as:

-

Feeling overwhelmed more easily

-

More anxiety

-

Emotional “reactivity”

-

Trouble sleeping

-

Losing your tolerance for stressors that used to feel manageable [5,9,18]

Life pressures in midlife often add another layer.

d) More inflammation and immune activation

Perimenopause is associated with:

-

Higher inflammatory markers

-

More oxidative stress

-

Changes in gut–immune interactions

These can worsen both physical and emotional PMS symptoms in already sensitive women [10,18].

e) BDNF and hormonally sensitive mood

BDNF is a brain growth factor involved in mood regulation.

In hormonally mediated conditions like PMDD and perimenopausal depression, BDNF patterns differ from traditional depression, suggesting overlapping biology [22].

This helps explain why many women describe perimenopausal mood symptoms as feeling very similar to the worst PMS they’ve ever had.

6. Who Is Most at Risk of Worsening PMS?

You’re more likely to notice PMS worsening in perimenopause if you have:

-

A past history of PMS or PMDD [17]

-

Depression or postpartum depression [18,19]

-

Early life trauma (especially before age 13) [23]

-

A sensitive stress system or high chronic stress [9]

-

Irregular cycles [16]

-

History of strong reactions to hormonal contraception, postpartum changes, or earlier ovulatory cycles

In these women, perimenopause acts as a magnifier of an already sensitive neuro-hormonal system.

7. Why Some Women Improve in Perimenopause

The good news is that many women feel better as they move through this transition.

Why?

-

Fewer ovulations mean fewer luteal phases

-

Less progesterone/ALLO cycling

-

Hormones eventually settle into a lower, more stable pattern

If your brain is less sensitive to hormone swings, emotional stability often improves dramatically once periods stop.

8. The Big Picture: You’re Not Broken — You’re Sensitive in a Turbulent Phase

PMS is not a character flaw and worsening PMS in your 40s (and even 30's) does not mean you’re failing to cope.

The truth is:

-

PMS and PMDD reflect a sensitive interaction between hormones, the brain, the stress system and the immune system

-

Perimenopause makes hormones more chaotic, amplifying this sensitivity

-

A subset of women — especially those with past PMS, depression, trauma or high stress — will feel this more intensely

-

Others will feel stable or even better as cycles wind down

Understanding the biology behind your symptoms is incredibly empowering. You’re not overreacting. You’re not imagining it. And you’re certainly not alone.

There are many ways to support your brain, hormones and stress system through this transition — and you deserve a plan that helps you feel like yourself again. Please reach out to your health professional if you need more support, there are lots of options!

This is part one- if you want to look at what actually helps in PMS take a look at this article.

References

-

Rapkin A, Akopians A. Pathophysiology of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Menopause Int. 2012;18:52–59.

-

Tiranini L, Nappi R. Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Faculty Reviews. 2022;11:11.

-

Itriyeva K. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescents. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2022;101187.

-

Modzelewski S et al. Premenstrual syndrome: new insights into etiology and review of treatment methods. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1363875.

-

Ayhan I et al. Premenstrual syndrome mechanism in the brain. Florence Nightingale J Med. 2021.

-

Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Allopregnanolone in PMDD: dysregulated sensitivity to GABA-A receptor modulating neuroactive steroids. Neurobiol Stress. 2020;12.

-

Ryu A, Kim T. Premenstrual syndrome: A mini review. Maturitas. 2015;82(4):436–440.

-

Kovács Z et al. Premenstruális szindróma és premenstruális dysphoriás zavar. Orv Hetil. 2022;163(25):984–989.

-

Kappen M et al. Stress and rumination in PMS: menstrual-cycle-related differences. J Affect Disord. 2022.

-

Granda D et al. PMS and inflammation, oxidative stress and antioxidant status. Antioxidants. 2021;10.

-

Roomruangwong C et al. The menstrual cycle may impact gut permeability and immune activation. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2019;10.

-

Isgin K, Buyuktuncer Z. Nutritional approach in PMS. Turk Hij Den Biyol Derg. 2017;74:249–260.

-

Allshouse AA et al. Menstrual cycle hormone changes with reproductive aging. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2018;45(4):613–628.

-

Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Menstrual cycle phase, menopausal transition stage and PMS symptom severity. Menopause. 2022;29:1269–1278.

-

Roomruangwong C et al. Lowered steady-state luteal progesterone predicts PMS. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2446.

-

Tawakoli M et al. PMS prevalence in women with irregular cycles. Int J Womens Health. 2025;17:1911–1922.

-

Freeman EW et al. PMS as a predictor of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2004.

-

Sander B, Gordon JL. Premenstrual mood symptoms in perimenopause. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23.

-

Gordon JL et al. Ovarian hormone fluctuation and HPA dysregulation in perimenopausal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):227–236.

-

Woods NF, Taylor-Swanson L. Depression and bleeding in menopausal transition. Menopause. 2012.

-

Baker L, O’Brien PMS. PMS: a perimenopausal perspective. Maturitas. 2012.

-

Harder JA et al. BDNF and mood in perimenopausal depression. J Affect Disord. 2021.

-

Woźniak R et al. Trauma history and mood sensitivity to estradiol fluctuation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017.

Want my best free resources

Pop your name in and I will send you to my VIP resource page- more great gut tips included.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.