How to reduce your inflammation through Lifestyle

Inflammation is often talked about as something “bad,” but at its core, it is one of the body’s most important protective tools. It is a natural defence mechanism that helps us fight infections, heal injuries, and alert us when something isn’t right. Without inflammation, our bodies would struggle to recognise harmful bacteria — even those responsible for something as simple as a skin infection — allowing them to spread unchecked and cause serious harm. In this way, inflammation is an essential survival response that humans have evolved to rely on (1).

Under healthy circumstances, inflammation is temporary and purposeful. This short-term response, known as acute inflammation, is beneficial. It activates immune cells, increases blood flow to the affected area, and supports repair and healing. The familiar signs — redness, swelling, pain, and warmth — are simply visible markers of the immune system doing its job exactly as it should (1).

The challenge arises when inflammation no longer switches off. In modern life, many people experience persistent, low-grade inflammation that quietly lingers over months or even years. This ongoing immune activation can occur even when there is no clear injury or infection to resolve. Over time, this unresolved inflammation can begin to damage healthy cells and tissues, disrupt metabolic processes, and contribute to long-term health problems (1).

A helpful way to think about inflammation is fire.

When carefully controlled, fire protects and sustains us.

When it burns out of control, it causes destruction.

It is this chronic, smouldering form of inflammation — rather than the short-term protective kind — that is now recognised as a major contributor to many modern diseases, and in some cases may sit at their root (1,2).

Health Conditions Linked to Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is associated with a wide range of health conditions, including:

-

Cardiovascular disease and stroke (3)

-

Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance (4)

-

Cancer (1)

-

Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders (5)

-

Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus (1)

-

Asthma, eczema, and psoriasis (6)

-

Chronic pain syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease (7)

-

Depression and other mental health conditions (1,8)

While inflammation is rarely the sole cause of these conditions, a large body of evidence suggests it is often a key underlying driver.

Meta-Inflammation: A Modern Inflammatory State

In the 1990s, researchers began to describe a particular pattern of chronic inflammation now known as meta-inflammation. This term refers to a low-grade, ongoing inflammatory state that is closely linked to excess energy intake, insulin resistance, and the way fat is stored in the body — especially visceral fat, which sits deep inside the abdomen around organs such as the heart and liver (9).

Importantly, body fat is not just a passive place to store energy. Visceral fat is biologically active and communicates with the immune system. As fat tissue expands, it releases inflammatory signalling molecules called cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). This process also attracts immune cells into the fat tissue itself, further amplifying inflammatory signals that circulate throughout the body (10).

Over time, this persistent inflammatory “background noise” plays a central role in the development of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disease.

Meta-inflammation is now recognised as one of the key biological links between excess body fat and chronic disease risk, helping to explain why metabolic health and inflammation are so closely intertwined (4,9).

Inflammaging: Inflammation and the Ageing Process

Another important concept is inflammaging, which describes the gradual rise in background inflammation that occurs with ageing (5).

Inflammaging reflects the cumulative impact of:

-

long-term immune activation

-

increasing visceral fat

-

reduced physical activity

-

sleep disruption

-

chronic psychological stress

-

changes in gut microbiota composition

Inflammaging is strongly associated with conditions such as cardiovascular disease, sarcopenia (the gradual loss of muscle mass), frailty, cognitive decline, and neurodegenerative disease. It can also contribute to some of the physical changes we notice with ageing, such as reduced skin elasticity over time (wrinkles). Importantly, the amount of inflammaging is not an inevitable consequence of getting older. Research shows that lifestyle factors — including nutrition, physical activity, sleep, stress management, and metabolic health — play a powerful role in shaping how much inflammation accumulates as we age (1,5).

Why Is Inflammation More Important in Perimenopause and Menopause?

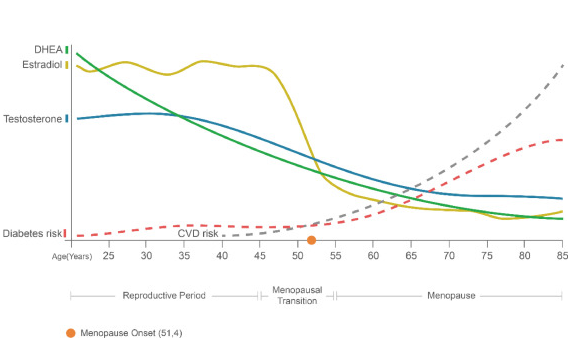

Hormonal changes during perimenopause and menopause have a meaningful impact on inflammation, and this helps explain why many women notice a shift in their health during this transition.

Oestrogen is not only a reproductive hormone — it also plays an important anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating role in the body. Under normal circumstances, oestrogen helps regulate inflammatory signalling by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6 and TNF-α), supporting endothelial (blood vessel) health, and improving insulin sensitivity (1,5).

During perimenopause, oestrogen levels become more variable, and over time, average oestrogen declines. After menopause, circulating oestrogen levels are significantly lower. This hormonal shift is associated with an increase in background inflammatory activity, reflected by rises in markers such as CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α (5,6).

This increase in inflammation is not simply an effect of ageing alone. Research suggests that the loss of oestrogen’s protective effects contributes independently to inflammatory activation, particularly in combination with changes in body fat distribution, insulin resistance, sleep disruption, and stress that often occur during midlife (5,9).

Clinically, this helps explain why postmenopausal women have a higher risk of:

-

cardiovascular disease

-

osteoporosis and accelerated bone loss

-

central (abdominal) fat gain

-

insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome

All of these conditions share inflammation as a key underlying mechanism (4,5,10).

Importantly, this does not mean that inflammation is inevitable or irreversible after menopause. Rather, it highlights why lifestyle strategies that reduce inflammation — including nutrition, physical activity, sleep optimisation, stress regulation, and body composition support — become even more impactful during this stage of life.

Understanding how hormonal changes affect inflammation can be incredibly freeing. It helps you step away from self-blame — from thoughts like “my body is failing me” — and move toward a more empowering way of seeing what’s happening. Your body is responding to real biological changes, not letting you down.

With the right support, small and targeted lifestyle changes can help restore balance, lower disease risk, and support your long-term health through perimenopause and well beyond it (1,5).

This graphs shows how chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes increase sharply after hormones drop off at the time of menopause.

https://www.maturitas.org/article/S0378-5122%2821%2900119-5/fulltext#fig0001

Symptoms of Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation often presents with vague, whole-body symptoms rather than obvious signs of infection. Common features include:

-

Persistent fatigue and low energy

-

Brain fog, poor concentration, or memory difficulties

-

Joint and muscle pain

-

Skin rashes or recurrent mouth ulcers

-

Mood changes, anxiety, or low mood (8)

-

Digestive symptoms such as bloating, reflux, or diarrhoea (8)

-

Unexplained weight gain or difficulty losing weight

-

Allergies or food intolerances

Metabolic syndrome is a term used to describe a cluster of cardiometabolic risk factors that tend to occur together. It is now widely recognised as an inflammatory condition, reflecting the close relationship between metabolism, insulin resistance, and chronic low-grade inflammation.

A diagnosis of metabolic syndrome is made when three or more of the following features are present (4):

-

Excess abdominal fat, particularly weight carried around the waist

-

High blood pressure

-

Elevated triglycerides

-

Low HDL (“good”) cholesterol

-

Insulin resistance, prediabetes, or type 2 diabetes

Understanding metabolic syndrome through an inflammatory lens helps shift the focus away from blame and toward supportive, lifestyle-based strategies that can meaningfully reduce risk and improve long-term health.

Testing for Chronic Inflammation

The most commonly used blood marker of chronic inflammation is C-reactive protein (CRP), particularly high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) (3).

-

Mild elevations of hs-CRP (approximately 1–10 mg/L) often reflect chronic, low-grade metabolic inflammation

-

CRP correlates with blood sugar control, lipid abnormalities, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular risk (3,4)

-

Very high CRP levels usually indicate acute infection or autoimmune disease

Other inflammatory markers, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, are primarily used in research rather than routine clinical care (1).

Nutrition, Gut Health, and Inflammation

Nutrition influences inflammation through many interconnected pathways in the body — including immune signalling, blood sugar and insulin regulation, gut health, body fat distribution, and even the way certain genes are switched on or off. This is why overall dietary patterns, rather than focusing on single “superfoods” or supplements, have the greatest impact on inflammation and long-term health (9).

Across large population studies and well-designed clinical trials, a consistent pattern emerges: people who eat higher-quality diets — especially those that are fibre-rich, minimally processed, and centred around plant foods — tend to have lower levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and related immune signals (9,11).

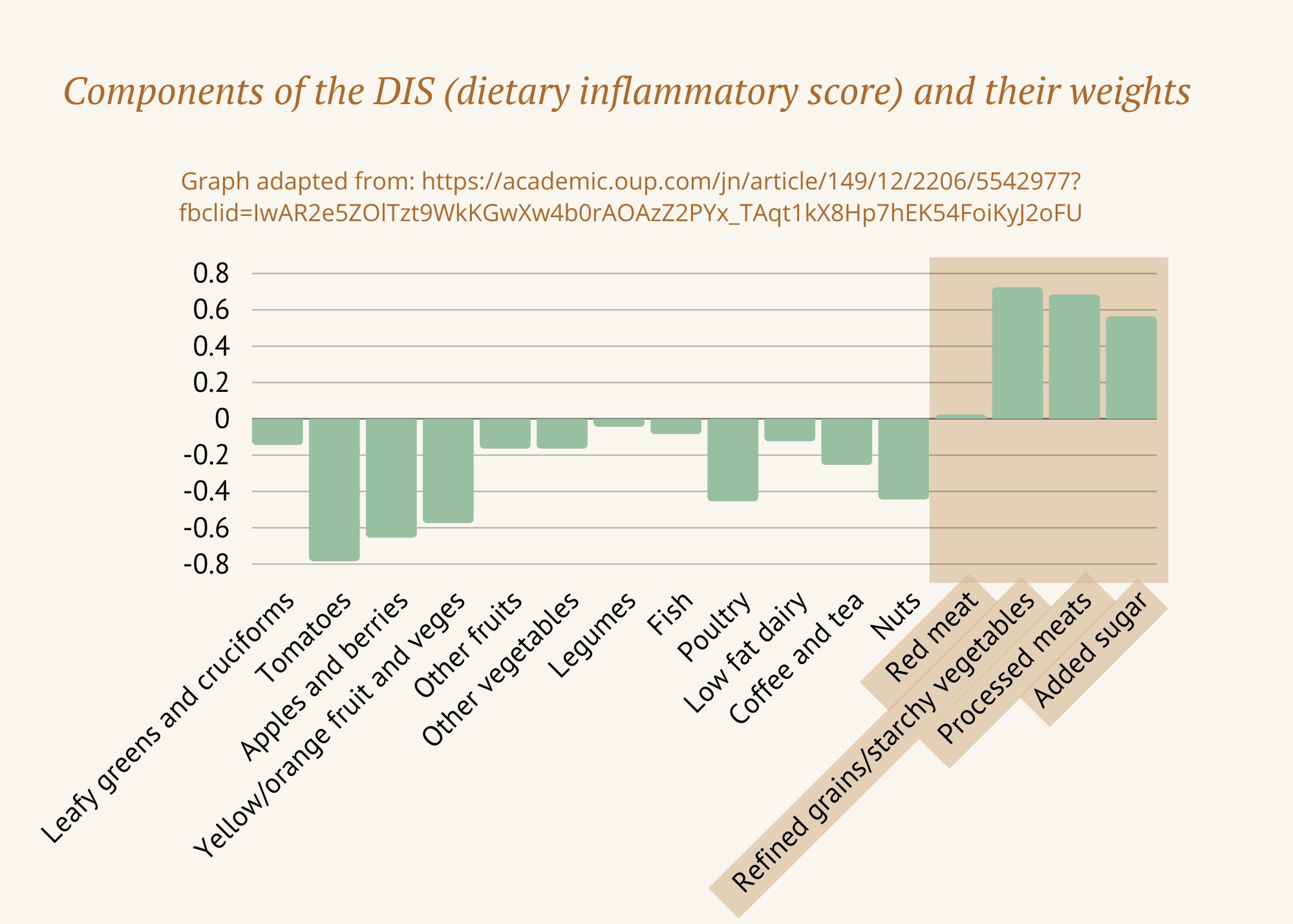

The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII): How Scientists Measure Food and Inflammation

Much of what we know about food and inflammation comes from research using a tool called the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII). The DII was designed to answer a simple but important question: how do different foods influence inflammation in the body?

Researchers developed the DII by analysing data from over 6,000 studies from around the world, examining how specific nutrients affect inflammatory markers in the blood, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and inflammatory cytokines. Because nutrients are easier to measure consistently than whole foods, the DII focuses on micronutrients and dietary components rather than individual meals.

The result is a validated, evidence-based scoring system that ranks nutrients according to how inflammatory or anti-inflammatory they are. It’s not a theory — it’s a tool that has since been used in hundreds of studies and multiple meta-analyses across a wide range of health conditions.

Research using the DII consistently shows that diets higher in inflammatory components are linked with higher rates of conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity, cancer, asthma, arthritis, mental health conditions, and hormone-related disorders including menopause, endometriosis, and PCOS. In contrast, diets with a more anti-inflammatory profile are associated with improvements in symptoms, disease activity, and inflammatory markers.

In simple terms:

-

More positive DII scores = more inflammatory

-

More negative DII scores = more anti-inflammatory

You can find the original DII table here – the more negative the score, the more anti-inflammatory a nutrient is, whereas more positive scores are more inflammatory.

Not surprisingly, the most inflammatory nutrients tend to come from highly processed and animal-heavy dietary patterns — including saturated fat, trans fats, refined carbohydrates, and excess total energy. Some nutrients found in animal foods, such as vitamin B12 and iron, score as mildly inflammatory — not because they are “bad,” but because excess intake, common in Western diets, can contribute to inflammation.

On the other hand, the most anti-inflammatory components consistently come from plant foods. These include flavonoids, isoflavones, vitamins, herbs and spices, green tea, and other polyphenol-rich compounds.

What this tells us — very clearly — is that a diet rich in whole, minimally processed plant foods and lower in refined and ultra-processed foods creates a more anti-inflammatory environment in the body, supporting overall health and resilience.

To make this research more practical, later studies used the DII data to rate whole foods based on their overall inflammatory potential. These food-based scores follow the same pattern: the more negative the score, the more anti-inflammatory the food; the more positive the score, the more it tends to promote inflammation. This makes the science far more usable in everyday life.

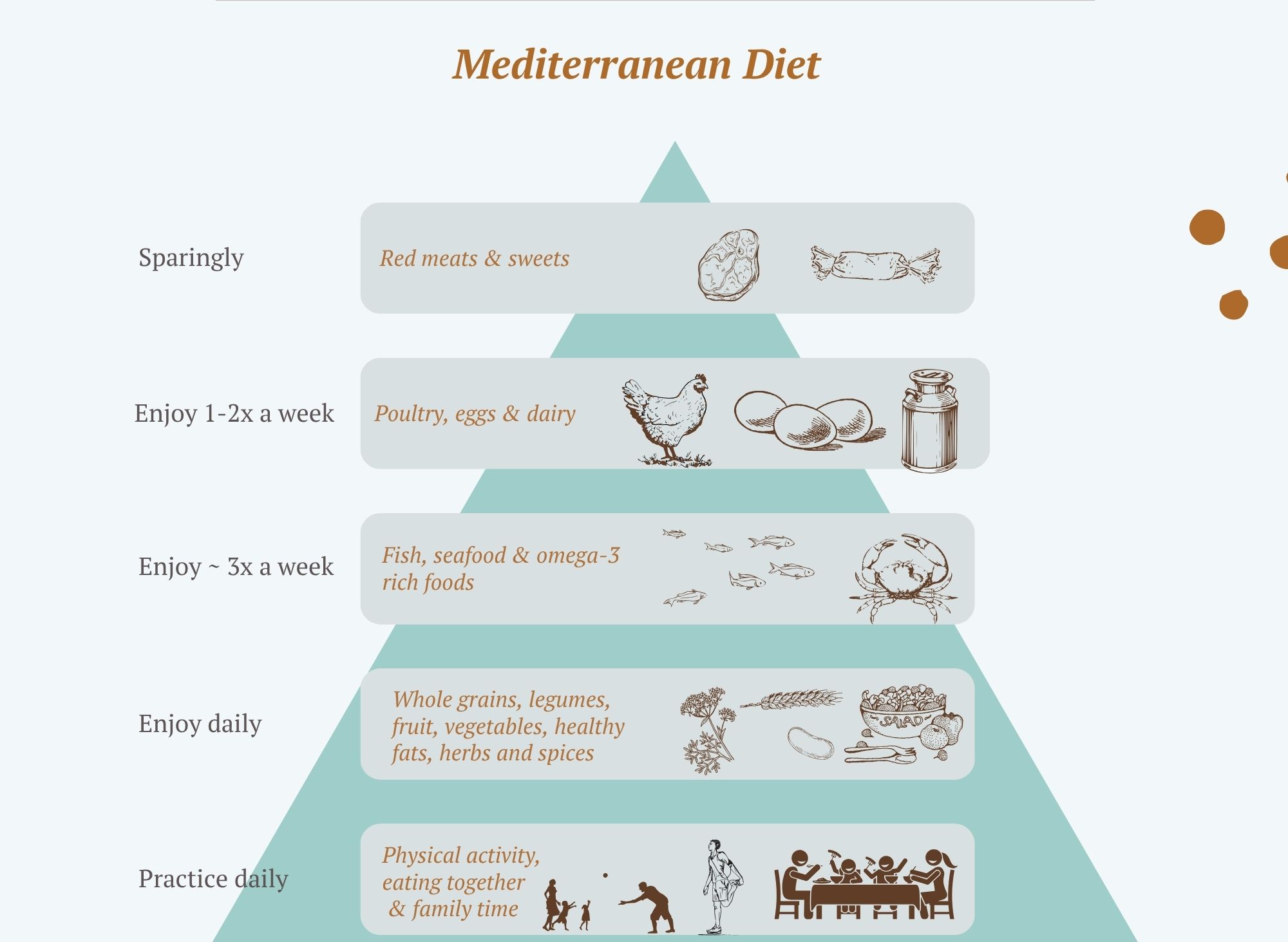

Eating in a Way That Calms Inflammation

When it comes to inflammation, it’s not about one “superfood” or cutting everything you enjoy. What matters most is the overall pattern of how you eat, day in and day out. Research consistently shows that certain eating styles create a calmer, more anti-inflammatory environment in the body — even without weight loss or perfection (09,11).

At the centre of this way of eating is a simple principle:

whole foods, mostly plants, minimally processed, and eaten regularly.

Dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet, plant-forward diets, and other traditional eating styles are repeatedly associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers like CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α, as well as lower rates of heart disease, diabetes, cognitive decline, and metabolic disease (09,11).

What This Looks Like in Real Life

An anti-inflammatory way of eating tends to include:

-

Plenty of vegetables, especially leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, kale, cabbage), and deeply coloured vegetables

-

Fruit, particularly berries and other colourful options

-

Legumes such as lentils, chickpeas, and beans

-

Whole grains like oats, brown rice, quinoa, and barley

-

Nuts and seeds, used regularly rather than occasionally

-

Extra-virgin olive oil as the main added fat, and oily fish for omega-3

-

Herbs, spices, tea, and coffee, which provide powerful plant compounds

This combination naturally provides fibre, polyphenols, antioxidants, and healthy fats — all of which work together to reduce inflammatory signalling and support gut and metabolic health (09,14).

Omega-3 Fats: Helping the Body Switch Inflammation Off

Omega-3 fats deserve special mention because they don’t just reduce inflammation — they help the body actively resolve it.

Omega-3s reduce the production of pro-inflammatory molecules and are converted into specialised compounds called resolvins and protectins, which help signal that the inflammatory response can calm down once it has done its job. In other words, omega-3s help the body turn off the fire, rather than letting it smoulder (11).

Higher omega-3 intake has been associated with lower CRP and inflammatory cytokines, as well as improvements in insulin sensitivity, cardiovascular health, joint symptoms, and brain health — all closely linked to inflammation (4,11).

Modern Western diets tend to be very high in omega-6 fats (from refined seed oils and ultra-processed foods) and relatively low in omega-3s. While omega-6 fats are not inherently harmful, this imbalance can promote a more inflammatory internal environment. Increasing omega-3 intake helps restore a healthier balance (09).

Food sources of omega-3s include:

-

Oily fish such as salmon, sardines, mackerel, trout, and anchovies

-

Plant sources like chia seeds, flaxseeds, hemp seeds, and walnuts

-

Algae-based omega-3s for those who don’t eat fish

For women who eat fish, aiming for 2–3 serves of oily fish per week is associated with anti-inflammatory benefits. For plant-based eaters, regular inclusion of seeds and nuts still provides meaningful support, even though conversion to the most active forms is lower (11). A good-quality fish oil or algae based supplement can also be considered.

Foods and Eating Patterns That Quietly Fuel Inflammation

Ultra-processed foods

Ultra-processed foods are designed for convenience and shelf life, not for nourishing our biology. Diets built around these foods tend to be low in fibre and protective plant compounds (polyphenols), and high in refined carbohydrates, industrial fats, salt, and additives. Over time, this combination disrupts the balance of the gut microbiome, reduces the production of anti-inflammatory gut compounds, encourages excess calorie intake, and drives meta-inflammation through increased body fat — often without people realising it’s happening (09,12).

Refined carbohydrates and frequent sugar spikes

Foods that rapidly raise blood sugar and insulin can place the body under ongoing metabolic stress. When this happens repeatedly, it increases oxidative stress and leads to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) — compounds that act like tiny sparks, switching on inflammatory pathways and contributing to tissue damage and metabolic dysfunction over time (13).

Common examples include:

-

White bread, white rice, and refined pasta

-

Pastries, cakes, biscuits, and baked goods

-

Sugary breakfast cereals

-

Sweets, lollies, chocolate bars

-

Soft drinks, fruit juice, and sweetened beverages

These foods are often easy to overconsume and are typically low in fibre, which further amplifies their inflammatory effects.

Poor-quality fats in a low-fibre diet

Dietary fats don’t act in isolation — the effect they have on inflammation depends heavily on the overall quality of the diet they sit within. Diets higher in saturated fats, especially when combined with low fibre intake and increased abdominal fat, are associated with higher levels of inflammatory markers (9).

Examples of foods commonly contributing to this pattern include:

-

Meat, especially fatty cuts

-

Processed meats such as sausages, bacon, ham, salami, and deli meats

-

Butter, cream, ghee, and full-fat dairy

-

Takeaway meals and fast food

When these foods crowd out fibre-rich plant foods, the inflammatory impact becomes more pronounced.

Trans fats: particularly inflammatory

Trans fats are especially harmful and deserve separate mention. Found largely in ultra-processed and deep-fried foods, trans fats are strongly pro-inflammatory. They increase inflammatory signalling, worsen insulin resistance, and raise cardiovascular risk. Unlike some fats that may be neutral in small amounts, trans fats offer no health benefit and actively fuel inflammation (09).

Common sources include:

-

Commercial baked goods (cakes, biscuits, pastries)

-

Fried takeaway foods (chips, fried chicken, donuts)

-

Margarines and shortenings made with hydrogenated oils

-

Many packaged snack foods

Low fibre intake

Low fibre intake is one of the most common — and most underestimated — contributors to chronic inflammation in modern diets. Without enough fibre, the gut microbiome loses one of its key fuel sources, the production of anti-inflammatory compounds falls, and inflammatory signalling quietly increases over time (09).

Diets low in fibre often look like:

-

Few vegetables or legumes

-

Minimal whole grains

-

Heavy reliance on refined or processed foods

In contrast, increasing fibre through vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds is one of the most powerful ways to support gut health and reduce inflammation.

Gut Health: Where Inflammation Is Set or Settled

The gut is far more than a digestive system — it is one of the body’s central immune hubs. In fact, it’s estimated that around 70% of the body’s immune system is located in and around the gut, where immune cells are constantly interacting with food, microbes, and environmental signals. This makes the gut a key decision-maker in whether the immune system remains calm and tolerant or shifts toward inflammation.

When the gut microbiome is healthy and diverse, it helps train the immune system to respond appropriately. It strengthens the intestinal barrier, supports immune tolerance, and produces anti-inflammatory compounds that influence inflammation throughout the entire body (14).

In contrast, Western-style eating patterns — typically low in fibre and high in processed foods — can disrupt this delicate balance. Over time, this can lead to dysbiosis (an imbalance of gut microbes) and increased intestinal permeability (often termed leaky gut). When the gut barrier is compromised, inflammatory signals such as endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) can pass into the bloodstream, triggering immune activation and contributing to ongoing, low-grade systemic inflammation (12,14).

Fibre: One of the Most Powerful (and Underrated) Anti-Inflammatory Tools

Fibre is one of the most reliable nutrients we have for calming inflammation. Across multiple large studies, people who eat more fibre consistently have lower levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and reduced systemic inflammation — and this relationship holds true across all body-weight categories (09).

But fibre doesn’t work alone. When fibre reaches the gut, it becomes food for beneficial microbes. These microbes ferment fibre into short-chain fatty acids, such as butyrate — compounds that help strengthen the gut lining, calm immune overactivity, improve insulin sensitivity, and reduce inflammation that originates in the gut and spills into the rest of the body (14).

Importantly, fibre’s benefits are not simply a side effect of weight loss. In the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, higher fibre intake was associated with reductions in inflammatory markers such as CRP and interleukin-6 (IL-6), even after accounting for changes in body weight. This suggests fibre has direct anti-inflammatory effects independent of weight loss (15).

A practical target to aim for:

-

Minimum: 25–30 g of fibre per day

-

Often beneficial: 30–40 g per day, if tolerated

Increasing fibre gradually and from a wide variety of plant foods helps maximise benefit while minimising digestive discomfort.

Fermented Foods

Fermented foods such as yoghurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, miso, and tempeh can support gut health by introducing beneficial microbes and bioactive compounds. Small, regular amounts may be helpful but for women with histamine sensitivity, reflux, or reactive IBS, prioritising fibre and plant diversity is more important than focusing on fermented foods.

Polyphenols: Plant Compounds That Gently Calm Inflammation

Polyphenols are natural compounds found in plants that help protect them from stress — and when we eat them, they offer similar protective benefits to us. You can think of polyphenols as some of the quiet helpers in plant foods: they reduce oxidative stress, help regulate inflammatory signalling, and support the growth of beneficial gut bacteria that play a key role in immune balance.

Rather than acting like a medication that targets one pathway, polyphenols work more subtly. They influence how certain genes involved in inflammation are expressed, help dampen excessive immune activation, and support metabolic health over time. This is one of the reasons diets rich in whole, colourful plant foods are so consistently linked with lower inflammation.

In the PREDIMED-Plus study, people who consumed higher amounts of polyphenol-rich foods showed improvements in inflammatory markers. These benefits were partly explained by improvements in metabolic health and body weight, highlighting how polyphenols work as part of an overall nourishing dietary pattern rather than in isolation (16).

Foods naturally rich in polyphenols include:

-

Berries (such as blueberries, strawberries, and blackcurrants)

-

Extra-virgin olive oil

-

Green tea and coffee

-

Herbs and spices (like turmeric, ginger, cinnamon, oregano, and rosemary)

-

Deeply coloured vegetables, especially reds, purples, and greens

A helpful way to think about polyphenols is to eat a rainbow. The more colour and variety on your plate, the broader the range of these protective plant compounds you’re likely to be nourishing your body with.

Lifestyle Strategies That Reduce Inflammation

Physical Activity: One of the Most Powerful Anti-Inflammatory Tools We Have

Movement is one of the most reliable and accessible ways to calm chronic inflammation — and it doesn’t require extreme exercise or perfection. Regular physical activity lowers inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) through several pathways: it reduces visceral (abdominal) fat, improves insulin sensitivity, enhances blood vessel function, and increases the release of anti-inflammatory signalling molecules from muscle tissue itself (4,11).

What’s especially encouraging is how responsive the body is to movement. Even relatively short-term increases in physical activity — over weeks to a few months — have been shown to reduce inflammatory cytokines, highlighting that benefits can begin well before weight or fitness changes are obvious (4).

Importantly, exercise does not need to be intense to be effective. Walking, cycling, swimming, resistance training, yoga, and other forms of regular movement all contribute to lowering inflammatory burden when practised consistently.

Evidence-based targets to aim for:

-

At least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity or

-

75 minutes per week of vigorous activity

-

Strength or resistance training at least twice weekly, which is particularly important for muscle health, metabolic resilience, and inflammation control

Sedentary Behaviour: Why Sitting Still Matters Too

Exercise alone is not the whole story. Prolonged periods of sitting have been shown to independently increase inflammatory markers — even in people who meet recommended exercise guidelines. Extended sedentary time raises levels of TNF-α and reduces anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, creating a more inflammatory internal environment (17).

This means that how often we move throughout the day matters, not just whether we exercise. Standing up, stretching, walking between tasks, or gently moving every 30–60 minutes can meaningfully reduce inflammatory signalling over time.

Sleep and Inflammation: The Night-Time Repair Window

Sleep is one of the body’s most important regulators of immune balance. During healthy sleep, cortisol levels naturally fall, body temperature drops, and melatonin — a powerful antioxidant — rises. This creates an internal environment that supports tissue repair, immune regulation, and inflammation resolution (1).

Even a single night of poor sleep can increase inflammatory markers the following day. When sleep disruption becomes chronic, it is strongly associated with higher rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and depression — all conditions with inflammation at their core (1,18).

A supportive target to aim for:

-

7–9 hours of good-quality sleep per night, recognising that consistency often matters as much as duration

Stress, the Nervous System, and Inflammation

Psychological stress is not “just in the mind” — it has direct biological effects on inflammation. Chronic stress activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic (“fight or flight”) nervous system. When this activation becomes prolonged, cortisol regulation becomes disrupted, paradoxically increasing inflammatory signalling rather than suppressing it (1).

Practices that calm the nervous system can meaningfully reduce inflammation. Mind–body interventions such as meditation, yoga, tai chi, breathing exercises, and other relaxation practices have been shown to reduce the expression of genes involved in inflammation and improve immune regulation (19).

Importantly, these practices do not need to look a certain way. Anything that reliably brings a sense of calm — quiet reading, time alone, gentle stretching, prayer, or mindful breathing — can support this anti-inflammatory shift.

Nature Exposure and Forest Bathing: A Simple, Powerful Reset

Spending time in nature is one of the simplest and most under-appreciated ways to reduce stress and inflammation. The Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, involves intentionally spending time in natural environments. Research shows that regular nature exposure lowers cortisol, blood pressure, and inflammatory markers, with measurable benefits seen even with once-weekly exposure (20).

This doesn’t require access to wilderness. Parks, beaches, gardens, or tree-lined streets can all provide meaningful physiological benefits.

Smoking, Alcohol, and Environmental Toxins

Smoking is a strong driver of chronic inflammation, increasing CRP and multiple inflammatory cytokines. Encouragingly, inflammatory markers begin to improve after smoking cessation, reinforcing that the body has a strong capacity to heal when exposures are reduced (9,11).

Alcohol consumption tends to cluster with higher inflammatory indices in population studies. While small amounts may not be harmful for everyone, from an inflammation perspective, less is generally better (9,11).

Environmental exposures also matter. Air pollution, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and other toxins activate immune pathways and contribute to chronic inflammation. Reducing cumulative exposure — even through small, practical changes — is biologically meaningful and supportive of long-term health (1).

The Power of Combined Lifestyle Change

One of the most reassuring findings in inflammation research is that no single habit carries all the weight. The strongest and most consistent reductions in inflammation occur when several lifestyle factors shift together — even modestly. Studies that look at combined lifestyle behaviours show a clear dose–response relationship: the more supportive habits a person has in place, the lower their overall inflammatory burden tends to be (4,9,11).

This means you don’t need to do everything perfectly. Each positive change — better sleep, more movement, more fibre, less stress, fewer harmful exposures — works alongside the others, gently nudging the body toward balance.

Final Takeaway: A Reframing That Matters

Chronic inflammation is not a personal failure. It is a predictable biological response to the way many of us are living — busy, overstimulated, under-rested, and often disconnected from our own needs.

The truly empowering truth is that inflammation is highly modifiable. Through nourishing food, regular and enjoyable movement, restorative sleep, nervous system support, time in nature, and reducing harmful exposures where possible, we can meaningfully calm inflammatory signalling and lower long-term disease risk.

You do not need to overhaul your life overnight. Small, consistent changes — repeated day after day — reshape the internal environment your cells live in. Over time, this creates the conditions for healing, resilience, and renewed energy to emerge.

Your body is not working against you. It is responding to the signals it receives — and with the right support, it has an extraordinary capacity to rebalance and thrive.

References

- Furman D, et al. Nat Med. 2019

- Liberale L, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022

- Ridker PM, et al. Circulation. 2003

- Wang A, et al. Front Public Health. 2025

- Franceschi C, et al. Ageing Res Rev. 2018

- Hart MJ, et al. Nutr J. 2021

- Rozich J, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020

- Millar S, et al. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2024

- Kantor ED, et al. PLoS One. 2013

- D’Esposito V, et al. Front Nutr. 2022

- Guo L, et al. Sci Rep. 2024

- Mundula T, et al. Curr Med Chem. 2022

- Navarro SL, et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016

- Ramos-López O, et al. Inflamm Res. 2020

- Herder C, et al. Diabetologia. 2009

- Rubín-García M, et al. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024

- Rodas L, et al. Nutrients. 2020

- Bhanusali N. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2025

- Black DS, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015

- Furuyashiki A, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019

Want my best free resources

Pop your name in and I will send you to my VIP resource page- more great gut tips included.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.